The Church as the Body of Christ

1992

|28|

Different metaphors depicting one or more facets of the church are used in the New Testament. An interpretation of the different metaphors will contribute to the assessment of the New Testament teaching on the unity of the church.

This chapter envisages to make such an interpretation of the metaphor „you are the body of Christ” in 1 Cor 12: 27. This isolation of the metaphor, however, is by no means a reconstruction of the metaphor into a model; it is merely a delimitation to facilitate the interpretation.

The metaphor „you are the body of Christ” consists of a tenor (you, i.e., the Church) and a vehicle (the body of Christ) (Grabe 1984:12).

When interpreting a metaphor it is important to keep in mind that a metaphor is no mere comparison, but that there is always an element of tension (Combrink 1986:226). The metaphor is no stylistic substitution; it is a redescription of reality (Clowney 1984:75), a fusion of two horizons (Combrink 1986:226); it, as Clowney (1984:103) puts it, „draws together two dissimilar contexts”, and therefore forces the interpreter to rethink reality and his view of both contexts.

Clowney (1984:103) is right when he stresses that metaphors are to be understood and interpreted in their context. When interpreting a metaphor, it is imperative that the imagination „is not freed to re-direct the metaphorical expression into other channels, but to pursue the depths of the biblical analogy” (Clowney 1984:102). For the interpretation of the vehicle it is necessary that its original horizon be regained if it is to serve its valid

|29|

metaphorical function (Clowney 1984:104). Therefore the first century understanding of „body” and „body of Christ” must be used as the grid in interpreting the meaning of the vehicle (in its original context), and its significance in the context of present day culture.

Therefore the contexts of the metaphor „you are the body of Christ” play a most important role in the interpretation of the metaphor. This pertains to the immediate context, but also to the wider context of the progressive history of redemption.

Only after the significance for the New Testament teaching on the unity of the church has been determined in this way, can the significance of the revelation for the present day church be explored successfully.

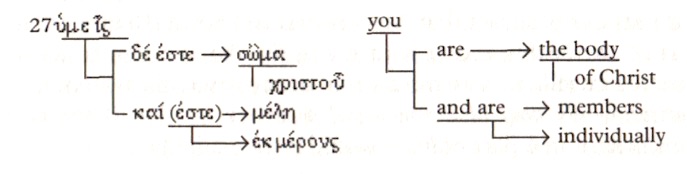

In the pericope 1 Cor 12: 12-31 the metaphor is used in a compounded way. Explicit use of the metaphor proper is found in 1 Cor 12: 27:

Since the whole pericope is an elaboration of this metaphor, it is necessary to make a careful analysis of the pericope in order to assess the relevancy of the metaphor for the New Testament teaching on the unity of the church.

V12: the basic statement, introducing the vehicle of the

metaphor

The basic statement is made in v12: „The body is a unit, though

|30|

it is made up of many parts; and though all its parts are many, they form one body. So it is with Christ” (NIV). Although the metaphor proper occurs only in v27, the vehicle of the metaphor (i.e., „the body” and „Christ”) is introduced in this introductory verse. There is as yet no genitive construction between „body” and „Christ”, but it is already evident from the contents that „body” and „Christ” are in some way connected.

V13: introduction of the tenor of the

metaphor

In v13, introduced by the particle gar, the author not

only states his reason for using the „body” symbol („For we are

all baptised by one Spirit into one body”), but he also

introduces the tenor of the metaphor, viz., „we”, i.e., all

believers, „whether Jews or Greeks, slave or free”.

Vv14-19: the reason for the diversity within a

body

In vl4 the reason for the diversity within a body is stated: „For

the body is not made up of one part but of many.” In vv15 & 16

the author states the implication of this diversity within the

body: the fact that the body is made up of different parts does

not imply that any one part ever ceases to be part of the body.

Verses 17-19 give three reasons for the statement that the body is made up of many parts: v17 argues that if there were not different parts, the body would not be able to perform all its functions; v18 reminds us of the fact that God created and arranged every single part of the body, and that in doing this he answers to no one except himself; in v19 the author summarises his argument by stating — by way of a rhetorical question — that if the body consisted of one part only, it would not be a body.

Vv20-24a: the unity of a body in spite of internal

diversity

Verses 20-24a form a new sub-section. In v20 the author

recapitulates the basic statement of v12 (cf. Robertson & Plummer

1967:274), focussing on the fact that the body, in spite of

internal diversity, is one. Paul then gives two implications of

this unity: in v21 he argues the interdependency of the parts:

since all the parts benefit when the body functions properly, the

different parts need each other.

In vv22-24a he points to the fact that the different parts require a

|31|

differentiated treatment for the „owner” of the body: exactly because the body functions as a unit, the „owner” is obliged to see to it that all the parts of the body function properly. This entails that he gives special attention and care to those members that need it in order to perform their functions.

Vv24b-26: the combination of the parts of the

body

Verses 24b-26 form another sub-section, parallel to vv21-24a.

This is again a recapitulation of the basic statement of v12, but

this time focussing on the combination of the different parts of

a body. In v24b Paul states that God has combined the different

parts of the body. There is therefore no room for a single part

to object to its role and function within the body; the part did

not get its role by mere chance, but by divine providence. And —

the author adds — God did not do this haphazardly; he gave

greater honour to the parts that lacked it.

In v25 God’s purpose with this specific combination of the parts of a body is stated: „so that there should be no division in the body, but that the parts should have equal concern for each other.” The result when the many parts of a body are thus combined, is stated in v26: „If one part suffers, every part suffers with it; if one part is honoured, every part rejoices with it.”

Vv27-31: application of the argument to the Corinthian

church

Verses 237-31 form the last sub-section of this pericope. The

argument of vv12-26 is applied to the Corinthian church. In v27a

the vehicle and the tenor of the metaphor, already introduced

respectively in v12 and v13, are identified, and the metaphor

proper is stated: „you are the body of Christ.” Immediately the

theme of the preceding is applied: „and each one of you is a part

of it” (Schneider 1967:596-7). Then the author adds the vertical

dimension, as he had done in v18 and again in v24b: „God has

appointed you in the church.” When interpreted in terms of the

metaphorical context, the author wants to convince his readers to

accept two things: that each one of them is part of the one body

of Christ; and that they must acknowledge the fact that God

himself assigned their role and function in the body to them.

In v28b Paul lists the different „parts of the body”, the different roles that different members are obliged to fulfil. By way of a

|32|

number of rhetorical questions he implies in vv29+30 that all the members can not perform the same functions.

Verse 31 is a conclusive exhortation: „Therefore eagerly desire the greater gifts.”

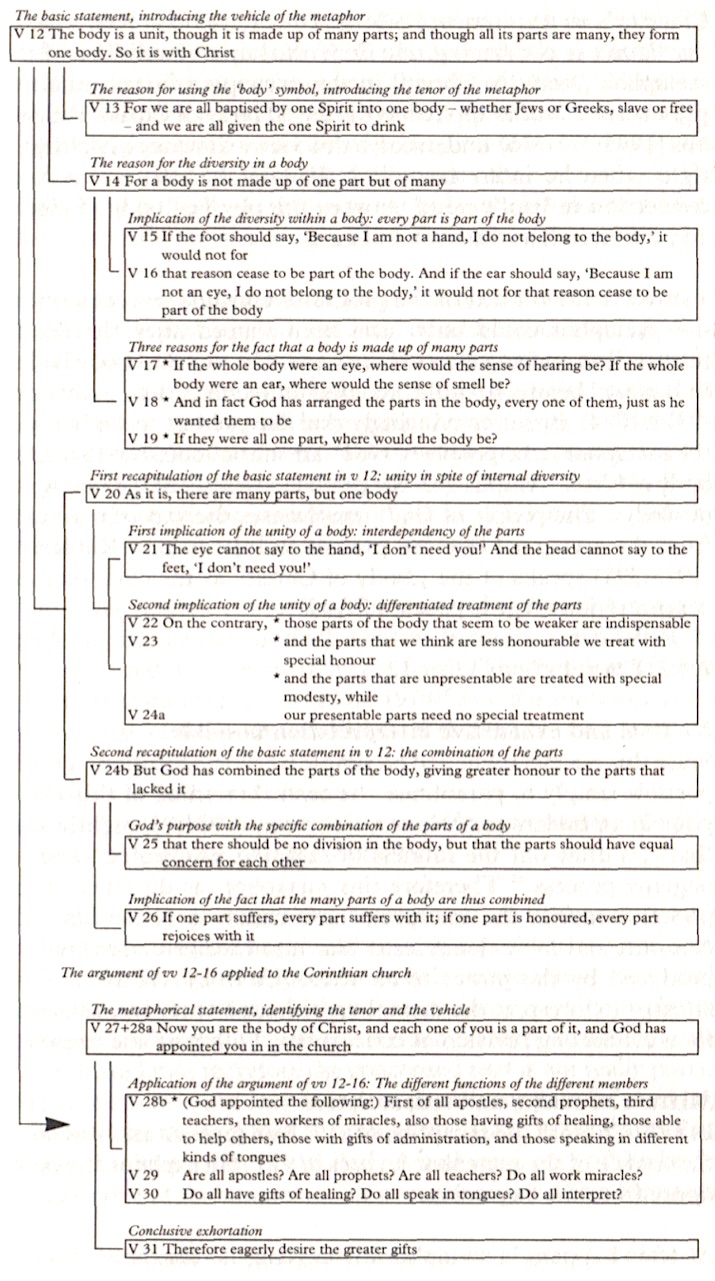

A synopsis of the structure of the argument

The following synopsis gives an overview of the flow of thought

in 1 Cor 12: 12-31 according to the preceding interpretation. The

thought structure has been partly symbolized by using blocks and

connecting lines. The text itself is put in the block. The

connecting lines indicate the portion of the preceding text with

which the present block is related, and the relation is defined

on the line immediately above the block (see synopsis on opposite

page 33).

It is quite clear from the context who the tenor, you, is: they are those who have been appointed in the church by God (v28a), who have been „baptised by one Spirit into one body”, and „who are given the one Spirit to drink”, „whether Jews or Greeks, slave or free” (v13). In 1: 2 Paul identifies his adressees as „the church of God in Corinth, . . . those sanctified in Christ Jesus and called to be holy, together with all those everywhere, who call on the name of our Lord Jesus Christ.” The you are therefore the faithful, the believers, the church in Corinth.

The vehicle, the body of Christ, must be interpreted against its historical scriptural setting.

Clowney (1984:85) observes that scholars have expended more effort in seeking the origins of this figure than in exploring its meaning. And after all the effort almost every part of Paul’s religious and cultural background has been isolated as the source of his use of this body figure.

|33|

|34|

Clowney's own argument (1984:85-86), after noting Paul’s use of the figure, is convincing. He finds the key to Paul’s use of the metaphor „body of Christ” in the principle of covenantal representation as it is applied to the literal body of Christ. Ridderbos (1975:375-376) underscores this view. Clowney (1984:86) is right when he infers from Eph 2: 13-16 that there is a close connection in Paul’s mind between the physical body of Christ and the church as the body of Christ.

Viewed in the context of the progressive history of redemption, this metaphor could only have been shaped after the death, resurrection and ascension of the Lord. His physical body had to be known before it could be used in a metaphor. Schweizer (1971:1074) argues convincingly that the present metaphor and the metaphor „the people of God” are at root one, but that „the body of Christ” emphasises the present character of the saving act of God. „The people of God” emphasises the way which leads from the saving act into the present and the future. Ridderbos (1975:395) speaks of the „body of Christ” as the christological concentration of „the people of God”.

No final and exhaustive interpretation

possible

Since this is a metaphor and no simple word-substitution, it is

not possible simply to paraphrase the central meaning of this

metaphor in an understandable way. Clowney (1984:96) rightly says

that „to draw out the fullness of meaning may prove to be an

ongoing process.” Therefore this metaphor (as do other metaphors)

compells the interpreter constantly to revise his conclusions,

and in so doing leads him into further understanding produced by

the power of its truth (Clowney 1984:97). This attempt to

interpret the metaphor, although tentative, also calls for a

continuing revision of conclusions, both past and present.

Mixture of reality and redescription

In vv 12-26 (with the exception of vl3) Paul gives an explication

of the vehicle of the metaphor he uses in v27. He explains the

body figure from the beginning.

As often happens in metaphorical language, so also here: it is not

|35|

always clear whether Paul has the physical body (any physical body or Christ’s physical body) in mind, or whether he is already speaking figuratively of the church as body (of Christ). Already in the introductory verse this interweaving is evident: he is comparing a physical body with Christ (kathaper to soma . . . houtoos kai ho Christos), and he immediately focusses the attention on the issues he will dwell on: the unity of the body, in spite of the fact that it is made up of many parts (cf. Schweizer 1971:1071).

Verse 13 is very important for the development of the argument. It defines the problem that Paul will be addressing in this pericope, viz. the relation between the diversity of the „we” (Greeks and Jews, and slaves and freed men) who have been baptised by the one Spirit and have all been given the one Spirit to drink. He hints at the solution of the problem when he mentions that the baptism by one Spirit was done into one body. In this way he in passing alludes to the metaphor proper of v27, before explaining the make-up of a physical body in vv 14-26.

One other remark concerning the unity of the church must be made: in vl3 the way in which a person becomes a member of the body is stated, viz., baptism by the Spirit. This baptism initiates one into the body of Christ (Floor 1979:58) and is therefore a sign of the unity of the body (cf. Fisher 1975:199).

Diversity in body and church

Verse 14 states that diversity within a body is inevitable: a

body is not made up of one part but of many.

In vv15+16 Paul is speaking figuratively. It is clear that he is already directing the argument towards a problem in the Corinthian church: some members deemed their own role in the church to be inferior. It seems as if they thought some roles in the church to be so inferior that they were not essential to the existence of the church, and that therefore the concerned part is not really part of the church. It is not only the more prominent parts of the body (the hand or the eye) that constitute the body. In vv15+16 Paul states that every part of the body is and stays part of the body, irrespective of its function or its own appraisal of this function.

In vv17-19 Paul emphasises the fact that a (physical) body is

|36|

necessarily made up of many parts. If that were not the case, the body would not be able to perform all its functions, such as hearing, seeing, smelling (v17). To think of a body as consisting of one part, is a contradiction (v19). With the rhetorical questions in vv29+30 Paul explicitly applies this figure to the church: in the church all the gifts have to exist and work.

In v18 and again in vv24b-26 the author stresses the fact that there is no haphazard arrangement and combination of the parts of a (physical) body; there is a very definite arrangement and combination, and this was done by God. No part of a body can therefore despise its place and role in the body; God himself arranged the parts of the body, giving greater honour to the parts that lacked it.

Paul explicitly applies this figure of the arrangement and combination of the parts to the church: after stating (in v27) that „you are the body of Christ, and each one of you is a part of it”, he emphatically adds: „and God has appointed you in the church.”

Unity in spite of internal diversity

In vv20-24a Paul emphasises the fact that the body is and stays a

unity in spite of internal diversity. After stating that the body

has many parts, but that this does not cancel the unity of the

body, he infers that this unity of the body necessarily implies

that the parts of the body are inter-dependent: the eye needs the

hand to function properly, and the head the feet (v21). This

argument is not explicitly taken up again in v27-31, but the

application to the church is evident: all the members in the

church need each other.

Verses 22-24a still dwell on the topic of the unity of the body, but now from the viewpoint of the body’s owner. The owner of the body must see to it that all its parts are in a position to function, otherwise the body itself will not perform properly. He knows that the seemingly weaker parts are indispensable (v22); he treats the parts deemed less honourable with special honour; and the unpresentable parts he treats with special modesty (vv22+23). The presentable parts are in no need of special treatment in order to function (v24a).

This argument on the differentiated treatment of the different parts of the body is not taken up again in vv27-31. In v24b God is

|37|

mentioned as giving greater honour to the parts that lack it; this, however, still pertains to the physical body in the first place (cf. Fisher 1975:204). In the context of the whole pericope and in the wider context of the Bible, the meaning is clear: God, or more specific, Christ is the „owner” of his body, the church. He wants his body to function properly, and therefore he differentiates his treatment of the parts, and this he does in the way explained in vv22-24a.

What is stated in v25 has important implication for the unity of the church. Verse 25 mentions God's purpose with his specific combination of the parts of a body: „so that there should be no division in the body, but that the parts should have equal concern for each other.” The result of such a combination of parts is that every part suffers when one part suffers, and that every part rejoices with one part when it is honoured (v26). It is therefore clear that the internal diversity does not and should not lead to a disruption of the unity, and that this is the case inter alia because God combined the parts of the body in the way he did.

Ridderbos (1975:369) is right when he says that Paul uses this metaphor with a clear paraenetic purpose. His statement is an imperative which rests on the indicative.

The unity of the church signifies both the internal unity of a local church (the intra-unity of the church), as well as the unity between different local churches (the inter-unity of the church). Snyman (1949) and Schmidt (1965:506-509) have convincingly argued, after studying the use of the word ekklesia, that revelation pertaining to the local church, is also applicable to the universal church (cf. Martin 1984:31). Therefore, what is said on an intra-level of the unity of the church, applies also to the inter-level. On the intra-level the „parts of the body” are the different members

|38|

of the church, and on inter-level the „parts of the body” are the different local churches. Both on the intra-level as well as on the inter-level the church — speaking in terms of the present metaphor — is „the body of Christ” (Grosheide 1957:334).

The fact that there are presently different denominations (as collections of local churches) finds no parallel in the New Testament. Whether the metaphor is also applicable to the interrelations of present day denominations, is a matter which needs further research.

In v13 baptism by the Spirit is stated as the way in which a person becomes a member of the body. This baptism can therefore be regarded as a sign of the unity of the church, both on the immunity level (cf. Van Wijk 1987:19), as well as the inter-unity level.

From v13 it is clear that when a person has become a member of the body of Christ, this membership supersedes both cultural/ethnic distinctions (Jews or Greeks) as well as social distinctions (slave or free) (cf. also Bosch 1979:1-2). This statement also holds true for the universal church: the cultural/ethnic or social uniqueness of a church is superseded in the unity of the church.

However small the role that a member plays in the church, that member remains a member in the same way as each part of the body is and stays an essential part of the body (vv15, 16). On the inter-level this means that a local church is and remains part of the church, however small or insignificant its role and function in the church.

Verses 17 & 19 show that without different members performing different functions and having different abilities, the church can not function properly. Just as all the functions of a body are not

|39|

performed by one part of the body, in the same way all the functions God demands from the church, are not and can not be performed by one member. It pleased God — speaking metaphorically — to make the one member the eye of the body, the other the ear, the other the nose, etc. Only when this diversity exits, can the body function properly.

These statements concerning the local church can be transposed to the universal church: different local churches performing different functions and having different abilities are essential for the proper functioning of the church. In the same way as all the functions of a body are not performed by one part of the body, so all the functions God demands from the church are not and can not be performed by any single local church. The body of Christ is made up of different churches, each with a specific role. This diversity is essential for the functioning of the body.

Any attempt to assign identical roles to all members in a local church (and to all the local churches), tampers with the essential diversity of the church, and this will result in a disfigurement of the body of Christ and the diminishing of its ability to function properly. Van Aarde (1987:325-351) is right when he describes the beginnings of the church as a history of reconciling diversity. The unity never means uniformity. The following statement by Schlink (1969:50) aptly underscores the point:

. . . we perceive the historical necessity for many concrete forms of proclamation, worship, dogmatic statements, etc. In these differences we also recognise one-sided aspects, inadequacies and corrections . . . But we also perceive that many one-sided aspects, inadequacies, and corrections complement each other and form an integral whole, despite the divisions. We perceive that God has not ceased to regard the churches as a whole, despite their separation . . .

From v18, it is clear that believers are appointed in the church by God. Their role and function are not to be decided horizontally, but vertically. And if a member desires another role and function, this should be petitioned from God (vv28+31) (cf. Grosheide 1957:339).

|40|

The same applies to the church on the inter-level: churches are allotted their place and role in the body by God. The fact that the role of a church is decided by God, does not imply that the church can not strive for another role. This should, however, be done in subjection to the will of God.

The members of the church are inter-dependent (v21) and need each other; the one member cannot function without the support of the others. This mutual support of the different members can take place only within the unity of the body, the church. Despite the diversity, the unity of the church therefore remains (v20). No member can function properly without being part of the one body.

The same applies to the church on the inter-level: the different churches (and denominations) are interdependent. The one church can not function without the support of the other. The unity of the body is a prerequisite for this mutual support to take place.

Christ is the owner of his body, the church. Christ wants his body to function properly. This can happen only when all the parts function properly. Therefore the owner gives special treatment to the members of the church who, because of their role or constitution, are in the greatest danger of not functioning properly. In metaphorical language these members are those that seem weaker (but are indispensable) (v22), those that are deemed less honourable (v23a) and those that are unpresentable (v23b). The other members need no special treatment. This differentiation is done for the sake of the body, all the members of the church.

What has been said pertaining to the local church, is also applicable to the universal church: Christ, the head of the church, differentiates his treatment of churches, giving special treatment to those that need it to function properly. This is not an injustice to the other churches; only when the „weaker”, „less honourable” and „unpresentable” churches are functioning properly,

|41|

does the unity of the body persist, and do all the member-churches get the full benefit of its functioning in unity. The differentiation thus actually benefits the whole body, all the members.

The fact that there is no division in the church must become evident (Ridderbos 1975:394, Van Wyk 1987:6-7 and Runia 1968:58). From v25 it is clear that this happens through the equal concern of the members for each other. The existence of the unity also becomes apparent if every member of the church suffers when one member suffers, and if every member rejoices when one member is honoured. This equal mutual concern serves as a touchstone for the existence of a unified church.

Again, this is also applicable to the church on the inter-unity level: on the one hand the churches' concern for each other testifies to the unity of the church. The absence of such mutual concern, on the other hand, testifies to a lack of acknowledgement of the unity of the church.

The metaphor points to the character of the unity: it excludes any idea of a mechanical unity. The body is an organism (cf. Van der Walt 1976:54); this implies that the unity is primary. It is not a result of the composition of different parts. It is a living unity which is more than the constituting parts.

This character of the unity applies both to the local church (the unity of the members), as well as to the universal church (the unity of the churches (or denominations)). The body of Christ is a living unity, and is not dependent for its existence on the different members; it exists as a living unity, because it exists in and because of Christ, and not vice versa (cf. Floor 1967:43 and König 1979:91).

When this is accepted, however much the unity is and must be sought, the process is never characterised by a feverish activity, as if the existence of the body of Christ is at stake. The unity must be

|42|

desired, but with peace of mind and tranquility because of the conviction that the unity of the body of Christ does exist (cf. Runia 1968:52+53); it is not a question of bringing this unity about, but of realising and experiencing it. This, however, should never be misunderstood as a reason for complacency; rather the undeniable reality of the indicative, places an enormous pressure on the imperative (cf. Runia 1968:63).

The significance of the metaphor „you are the body of Christ” for the New Testament teaching on the unity of the church is the following:

1. The unity of the church is an indicative and an

imperative.

2. The revelation pertaining to the unity of the church applies

to both the local and the universal church.

3. Baptism by the Spirit is a sign of the unity of the

church.

4. Earthly distinctions are superseded in the church.

5. An inferior role does not cancel membership of the church.

6. Diversity within the church is essential for its

functioning.

7. The appointments in the church are made by God.

8. The inter-dependence of the members of the church necessitates

unity of the church.

9. Christ differentiates in his treatment of members of the

church.

10. The unity of the church must manifest itself outwardly.

11. The unity of the church is of an organic and not a mechanical

character.

12. Further research must determine how the metaphor is

applicable to the inter-relations of present day denominations.

Barnard, A.C. 1971. „Die lewende kerk volgens die Skrif”.

Die Nederduitse Gereformeerde Theologiese Tydskrif 12,

161-266.

Berkhof, H. [s a]. Gods ene kerk en onze vele kerken.

Nijkerk: GF Callenbach NV.

Best, E. 1955. One body in Christ: a study in the

relationship of the church to Christ in the epistles of the

apostle Paul. London: SPCK.

Bosch, D.J. 1979. „Die nuwe gemeenskap rondom Jesus van Nasaret,”

in

|43|

Meiring & Lederle, Die eenheid van die kerk,

1979: 1-5.

Botha, C.J. 1979. „Calvyn se siening oor die eenheid van die

kerk”, in Meiring & Lederle, Die eenheid van die kerk,

1979:32-43.

Cerfaux, L. 1959. The church in the Theology of St.

Paul, translated by G. Webb & A. Walker. New York: Herder &

Herder.

Clowney, E.P. 1984. „Interpreting the biblical models of the

church: a hermeneutical deepening of ecclesiology,” in Carson, DA

(ed), Biblical interpretation and the church: text and

context, 64-109. Exeter: The Paternoster Press.

Coetzee, J.C. 1965. Volk en godsvolk in die Nuwe

Testament. Potchefstroom: Pro Rege.

Combrink, B. 1986. „Perspektiewe uit die Skrif,” in Kinghorn, J

(ed), Die NG Kerk en Apartheid, 211-234. Johannesburg:

Macmillan South Africa.

Du Plessis, I.J. 1962. Christus as hoof van kerk en

kosmos. Groningen: VRB.

Fisher, F. 1975. Commentary on 1 & 2 Corinthians. Waco:

Word Books.

Floor, L. 1967. Die formule ‘in Christus’ by Paulus.

ThM-thesis, Potchefstroom University for Christian Higher

Education.

Floor, L. 1975. Hy wat met die Heilige Gees doop.

Pretoria: NG Kerkboekhandel.

Gereformeerde Kerke in Suid Afrika. 1988. Agenda van die

drie-en-veertigste sinode te Potchefstroom op 5 Januarie 1988 en

volgende dae. Potchefstroom: Die Gerefor-meerde Kerke in

Suid-Afrika.

Gräbe, I. 1984. Aspekte van poetiese taalgebruik: teoretiese

verkenning en toepassing. Potchefstroom: Sentrale

Publikasies.

Groenewald, E.P. 1971. Die eerste brief aan die

Korinthiërs. Kaapstad: NG Kerk-uitgewers.

Grosheide, F.W. 1957. De eerste brief aan de kerk te

Korinthe. Kampen: J.H. Kok N.V.

Houtepen, A. 1979. „Koinonia and consensus: towards communion in

one faith,” The Ecumenical Review 31, 60-63.

König, A. 1979. „Modelle van kerkeenheid,” in Meiring & Lederle,

Die eenheid van die kerk, 1979:89-101.

Martin, R.P. 1984. The Spirit and the congregation: studies

in 1 Corinthians 12-15. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

Meiring, P. & Lederle, H.I. (eds) 1979. Die eenheid van die

kerk. Kaapstad: Tafelberg.

Moore, W.E. 1964. „One baptism,” in New Testament

Studies 10, 504-510.

Ridderbos, H. 1975. Paul: an outline of his theology,

translated by J.R. de Witt. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

Robertson, A. & Plummer, A. [1914] 1967. A critical and

exegetical commentary on the first epistle of St. Paul to the

Corinthians. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark.

Runia, K. 1968. Reformation today. London: The Banner of

Truth Trust.

Schlink, E. 1969. „The unity and diversity of the church,” in

Groscurth, R. (ed), What unity implies: six essays after

Uppsala, 33-51. Geneva: World Council of Churches.

Schmidt, K.L. 1965. s v ekklesia. TDNT.

Schweizer, E. 1971. s v soma. TDNT.

Snyman, W.J. 1949. Die gebruik van die woord „kerk” in die

Nuwe Testament. Potchefstroom: CJBF.

Spoelstra, B. 1986. „Het ons kerkwees in strukture gestol?”

Hervormde Teologiese Studies 42, 94-109.

Theron, P.F. 1979. „Die kerk as eskatologiese teken van eenheid,”

in Meiring &

|44|

Lederle, Die eenheid van die kerk, 1979:6-13.

Van Aarde, A.G. 1987. „Gedagtes oor die begin van die kerk — ’n

geskiedenis van versoenende verskeidenheid.” Hervormde

Teologiese Studies 43, 325-351.

Van der Walt, J.J. 1976. Christus as Hoof van die kerk en die

presbiteriale kerk-regering. Potchefstroom: Pro Rege.

Van Wyk, J.H. 1986. „Bavinck oor kerkeenheid.” In die

Skriflig 20, 43-44.

Van Wyk, J.H. 1986a. „Kerklike kontak oor kultuurgrense heen.”

Die Almanak van die Gereformeerde Kerke In Suid-Afrika

112,215-219.

Van Wyk, J.H. 1987. Kerkeenheid: ’n perspektief op die

verhoudinge in die gerefor-meerde Kerke in Suidelike Afrika.

(Paper presented at a meeting of the Gerefor-meerde Teologiese

Vereniging, Pretoria).

Visser ’t Hooft, W.A. 1956. The renewal of the church.

Philadelphia: The Westminster Press.

Wansbrough, H. 1968. Theology in St. Paul. Notre Dame:

Fides Publishers.